Film classic reboot: Paris, Texas – still a haunting tale of loss and redemption

It took a German filmmaker to produce the quintessential American road movie and 40 years on the 4K restoration of Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas has a definite thumbs up for standing the test of time.

It’s been 20 years since I last saw Wim Wenders’ 1984 Palme d’Or-winning film Paris, Texas. I think it was downstairs in the little cinema at Metro Arts (long gone now) and the film print looked – to borrow a memorable line from the film – like “forty miles of rough road”.

Thankfully, for the 40th anniversary, Wenders has overseen a meticulous 4K restoration. Still, I was apprehensive about seeing it again. Paris, Texas is one of those films that haunts your memory and, like a memory, it’s sometimes hard to know what you actually saw and what you thought you saw. It’s a common risk revisiting a half-forgotten classic decades later: Was it really as good I remembered?

Yes. Yes, it was.

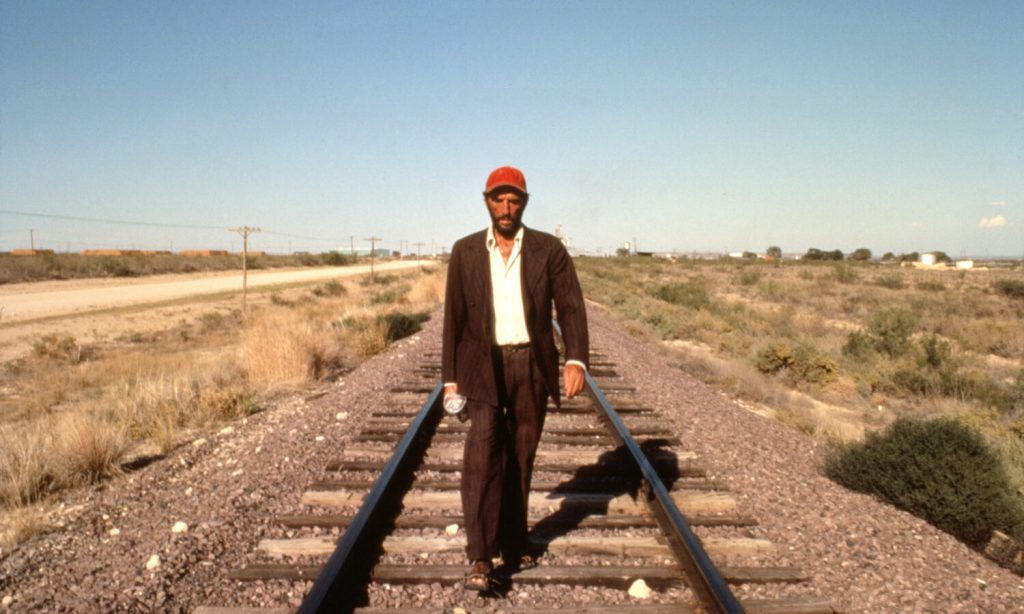

Directed by German auteur Wim Wenders and written by legendary American playwright and actor Sam Shepard, the film opens on a shabby, weather-beaten man walking through an unforgiving desert. He has a face that looks like it was carved out of a burnt log. The man’s name is Travis (played with subtle tenderness by Harry Dean Stanton) and we don’t know where he’s been or where he’s going. As it turns out, neither does he.

After collapsing from dehydration at a roadhouse, Travis is reunited with his brother, Walt (Dean Stockwell), who has been looking for him for four years. Walt has been caring for Travis’ young son, Hunter (Hunter Carson) after Travis’ wife, Jane (Natassja Kinski), dropped him off one day and never returned.

You might like

Where has Travis been? Why is he out here? What happened to him? Where is Jane? But Travis can’t explain because he can’t talk. He’s mute and it’s not clear if he remembers anything.

From this point the mysteries of the story roll out at an unhurried pace, like tumble weeds delivered by a soft desert wind, as Travis, and eventually his son, Hunter, hit the road in search of answers.

Road movies are a staple of American cinema so it’s ironic it took a German director to get this close to perfecting the form. Paris, Texas is a rare sort of cinema that feels as delicate and vulnerable as its characters who each try, and fail, to connect to each other using imperfect technologies – crumbling photographs, family movies, toy walkie talkies, crackling telephone lines.

Like a lot of classic cinema, the fact that Paris, Texas works as well as it does comes down to an uncanny convergence of talent arriving in the same place, at the same time, with exactly the right story to tell.

Subscribe for updates

Wenders, fresh off his 1982 US debut, Hammett (after being hired by Francis Ford Coppola), was eager to continue his fascination with Americana. Sam Shepard, having won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing, was in hot demand as a writer and actor. Harry Dean Stanton, following minor but memorable roles in The Godfather (Part 2) and Alien, was looking for a lead role to show off his talents.

Add to the team the captivating Natassja Kinski (daughter of German star Klaus Kinski) and brilliant Dutch cinematographer Robbie Müller, and the stage was set for a modern classic. Even the young assistant director, future French auteur Claire Denis, was pedigree.

The only thing they didn’t have was a finished screenplay.

Shooting the story in order, across five short weeks, Wenders and Shepard had riffed on an idea about a man who had lost his memory. But before they had finished the script, Shepard was called away to another job. Wenders recruited actor and writer L.M. Kit Carson (the father of the actor playing Travis’ son), to help devise an ending. The resulting last act of the story, with monologues written and dictated by Shepard over the phone to Wenders’ on-set secretary, is a work of heart-breaking genius.

The restored 4K print is gorgeous, showing off Müller’s masterful use of natural lighting while Ry Cooder’s iconic slide-guitar soundtrack shimmers over the film’s dusty landscapes like an aural heat haze.

The tonal range of the film remains remarkable – at times gently poetic, often whimsical, even funny, as well as dark and troubling. It’s an emotional journey and some modern audiences will wrestle with the subtle undercurrent of violence in the film’s mysterious backstory, as well as the sad, lonely redemption Travis is given by the end. But, like the town of its title, a place that is never seen, only alluded to, Paris, Texas works best in the open spaces it creates.

It was interesting seeing Wenders’ most recent film, Perfect Days, set in modern-day Tokyo, and recognising Travis in the film’s quiet and lonely main character, a man haunted by a distant trauma that shadows his journey through each day.

Paris, Texas, like Perfect Days, reaches for, and achieves, a sense of healing that reminds us of cinema’s enduring power as a storytelling medium.

The 40th anniversary 4K restoration of Paris, Texas, released by Madman Entertainment, is in selected cinemas from October 31 (including Palace Barracks, Brisbane).